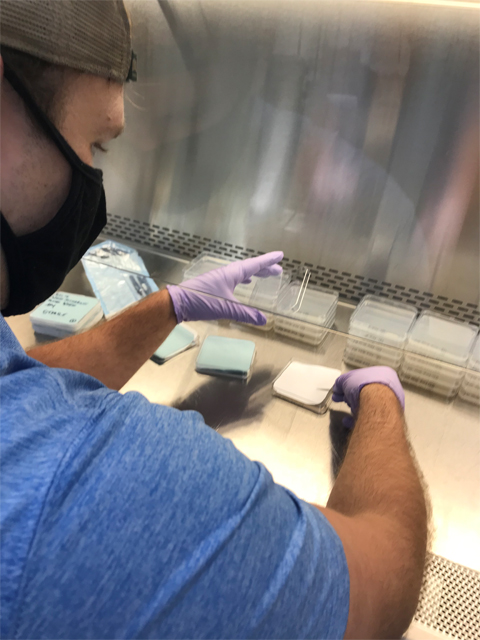

Two Ohio University plant biologists spent Aug. 25-26 at Kennedy Space Center in Florida for a Science Verification Test (SVT) in preparation for their upcoming flight to the International Space Station.

Actually, it’s not that Dr. Sarah Wyatt and Ohio University alumnus and post-doctoral researcher Dr. Alexander Meyers are making the trip to space themselves. It’s their research experiment that’s boarding a SpaceX rocket come springtime—though both researchers dream of someday making the leap beyond gravity themselves.

And gravity is why their research is headed to space.

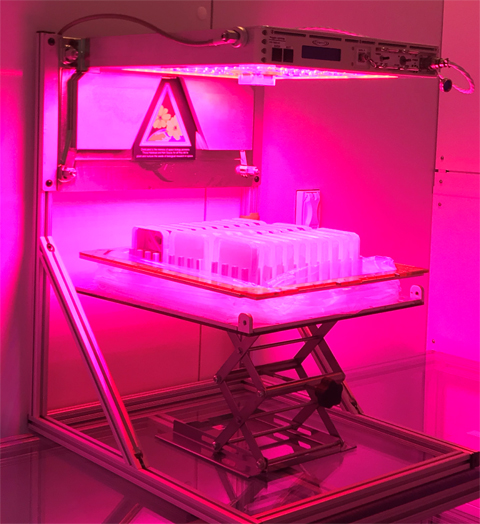

The Wyatt Lab experiment will take a ride on a SpaceX rocket to the International Space Station where it will be placed in an expandable Veggie unit like this one set up for SVT at Kennedy Space Center–complete with a red and blue LED lights to help the plants grow.

This will be their third in a succession of experiments exploring the effect of gravity on plants—which is essential to how humans might grow plants for food and medicine in environments with little or no gravity. Joining them on the SVT is their collaborator Eric Land, a graduate student in Dr. Imara Perera’s lab at North Carolina State University.

Already Wyatt’s lab has been isolating parts of the genetic code that govern how plants respond to gravity—for it is gravitational force and not sunlight that causes plant to grow up.

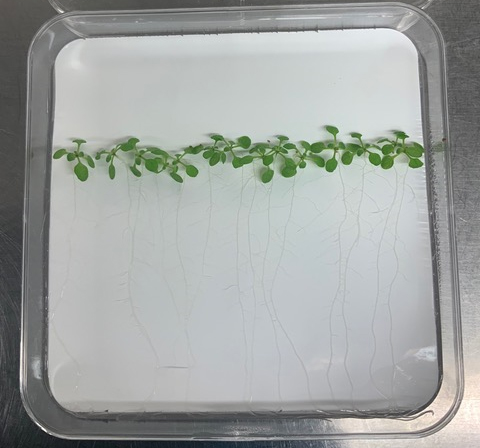

The lab’s first experiment involved germinating seeds in the micro-gravity environment aboard the space station. Those seeds sprouted for a few days in dark petri dishes and then were frozen, awaiting their return flight back to Earth.

Their spring spaceflight will send more Arabidopsis seeds to the ISS, but this time the seeds will sprout in “veggie units” that have enough moisture and light for the plants to grow for 12 to 14 days before they are frozen.

That’s long enough for the tiny plants to shoot up a stem. Actually, the shoots on these plants might not go “up;” they might go in many different directions without the navigational guidance of gravity.

The molecular biologists in Wyatt’s lab will be looking at gene expression in the roots and shoots of the plants this time, but she hopes to design a future experiment where the plants can flower, seed and then grow for several generations.

“That would give us a very good look at how the plants respond to the stress of micro-gravity. It’s very easy to make a plant bolt (or produce a flower stalk). Plants bolt when they are stressed—like a survival mechanism to produce a seed quickly to ensure the species carries on. But the resulting seeds and fruit can be small and not very abundant,” Wyatt says.

“If you’re trying to feed people on a space ship, we need to understand how to reduce the stress so that the plants produce high-quality fruit and vegetables.”

The researchers in the Wyatt lab focus on gene expression and how that expression changes depending on environmental stress. Genes (pieces of DNA) are transcribed to RNA then RNA is translated into proteins; it’s those proteins that do all the work. That’s what we really care about: what proteins are made. For years, scientists thought that all RNA that was transcribed was translated into proteins, so sequencing RNA was used as a proxy for proteins. But it’s not that easy. Just because RNA is made doesn’t mean it will be translated into protein.

The RNA sequencing data from that first spaceflight experiment (BRIC20) suggest that post-transcriptional regulation plays an integral role in gene expression differences between spaceflight and ground controls.

“The differential expression, abundance and phosphorylation of translational machinery in spaceflight leads to the obvious questions: What genes are being post transcriptionally regulated and by what mechanism(s)?” Wyatt notes. “This experiment may give us at least part of the answer to that question.”

NASA announced on Aug. 7 that Wyatt received an award for plant biology studies, with another spaceflight to the International Space Station in her lab’s future as the United States prepares for missions to the Moon and Mars.

Comments