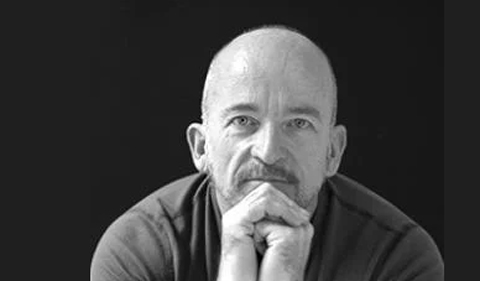

Mark Doty

Learn more about Mark Doty’s work and Lit Fest events here.

by Tatiana Radujkovic

The poet Mark Doty ensnares moments of plain humanity in stanzas of striking beauty, and his Fire to Fire: New and Selected Poems identifies and explores the world that surrounds us with a drollness, but also a distinct sense of tragedy. With this mix Doty performs a kind of everyday empathy.

In his poem “Citizens,” Doty mentions crossing the street and nearly being run over. At the thought of the strangers around him remaining oblivious to his own fumbling, too caught up in troubles of their own, he recalls a story about a monk going against his own beliefs to carry a weeping, old woman across a river. The monk’s friend later asks him, “How could you touch her when you vowed not to?” and the first monk responds, “I put her down on the other side of the river, why are you still carrying her?” In those few lines, Doty investigates what we carry, and who will carry us, and he expands his private moment of peril into a wider meditation on what we owe each other, on the successes and failures of empathy.

This concern shines through his many excellent collections of poetry, including Fire to Fire, which received the National Book Award, and his talent has resulted in many honors, including the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction for Heaven’s Coast, a memoir about the year after a beloved partner of Doty’s tested positive for the HIV in 1980s New York. His nonfiction is characterized by frankness and clear-eyed passion, and his other memoirs include Firebird, Still Life with Oysters and Lemon: On Objects and Intimacy, and Dog Years. The writer of numerous collections of poems, including Theories and Apparitions, Paragon Park, and Deep Lane, he is currently serving as a Distinguished Writer at Rutgers University.

With any writer as prolific and fascinating as Doty, it can be difficult to completely unravel the intricacies of the poems, but the strength, from my perspective, lies in their relatability. In an interview with Poets & Writers Magazine, Doty discussed how he cannot write as a “representative” for any group of people as it ultimately undermines the poem. He said, “I need to write about the particular circumstances of my life [ . . . ] and my life was a part of a larger fabric and I was responsible to that greater narrative.”

Doty’s writing is always aware of that greater narrative without giving up the truth of his own personal experiences. In reading him, we can find something of ourselves in his imagery, his open-mindedness.

Art, especially a form as intimate and personal as poetry, opens a door for readers to receive catharsis and to escape from the troubles plaguing them. Doty’s work—its wonder and imagination—allows that partial escape for its readers, allows them to set that woman down on the other side of the river and leave her there. It depicts and inspires grace and generosity, and as we go through phases of our lives—in unsettling times—we are lucky to have the challenging comfort provided by Mark Doty. His empathy allows us to understand ourselves better, to witness our own pain. And he gives us the vocabulary to carry, and to release, some of our beautiful-terrible burden.

Comments