Dr. Judith Grant and Dr. Vince Jungkunz

by Kristin M. Distel

Dr. Judith Grant, Professor and Chair of Political Science, and Dr. Vincent Jungkunz, Associate Professor of Political Science, recently published a co-edited volume, Political Theory and the Animal/Human Relationship, with State University of New York Press (Albany).

Grant and Jungkunz share an interest in destabilizing the idea of human exceptionalism, which, in part, gave rise to the volume. The intersection between political theory and the animal/human relationship has personal and academic foundations for them both.

OHIO Students Participate in the Animal/Human Conversation

Grant and Jungkunz began working on the book and soliciting chapters in spring of 2012.

Their current work at Ohio University has certainly informed the book, Grant and Jungkunz note, especially in terms of the classes they have taught and the students with whom they have worked. Grant points to her students in her animal/human machine course as having especially engaged in the topics that arise in the book and particularly in her chapter, “Darwin and Freud’s Posthumanist Political Theory.”

“Students have come back and said the course was inspiring and that it gave them a sense of direction for their own futures and careers,” Grant says. “As their professor, that’s so motivating and exciting.”

Jungkunz’s students have also benefited and contributed to his thoughts on the animal/human binary.

“Through classroom discussions, the community that the students and I create during a given semester has inspired, within me, new ways to extend my work on injustice; for instance, this book and my chapter have been influenced by classroom conversations about inequality and the devastation of dominant identities,” Jungkunz states.

‘The Silence of the Lambs’

Jungkunz’s chapter, titled “The Silence of the Lambs,” considers the ways in which humans have historically silenced animals’ voices and ignored animals’ needs and best interests.

“For my chapter,” Jungkunz says, “I continue to explore the various silences that are part of our political life, and silences that might be highlighted as useful ways to better participate democratically. Therefore, I argue that we, as dominant ‘humans’ are also privileged speakers; in fact, it is, according to many, our speech that is the fundamental characteristic separating us from animals and establishing our superiority.”

Jungkunz adds that humans’ “obsession with speech and incessant talking” prompts us to ignore animals’ voices.

“Animals are not silent, yet we treat them as such—we have silenced them, therefore ignoring their screams as they are subjected to the slaughterhouse, for instance. I argue that we need to elevate ‘silent yielding’ as a democratic practice that may open up new discourses from which we ‘humans’ can hear ‘animals’ anew,” Jungkunz remarks.

Origins of the Volume

The idea for the book began with Grant’s research and her involvement in animal rights projects. Grant has been involved for most of her adult life in animal rescue and animal welfare concerns, and she started to develop a course having to do with animal rights approximately 15 years ago at a different institution.

At OHIO, she developed that course more fully in order to teach students about posthumanist theory and the relationship among animals, humans, and machines.

Grant noticed that many political theorists begin their analyses by explaining what it means to be human and then emphasizing humans’ supposed superiority over animals.

This results in a definition by negation, Grant explains, in which writers outline what it means to be an animal, followed by summarily stating, “But we’re something better.”

“The animal/human relationship has been used not only to allow humans to dominate and kill animals, it has also been used to ‘dehumanize’ various groups of people in order to maintain powerful discourses and groups such as ‘white supremacy,’ ‘dominant masculinity,’ and ‘human exceptionalism,’” Jungkunz adds. “Throughout history, ‘human’ superiority has been a hegemonic assumption—humans are superior to animals.”

‘The Animal/Human Binary Has Been Devastating for Animals’

Grant and Jungkunz’s co-edited volume suggests alternatives to this supposedly firm boundary between humans and animals.

“There’s been an explosion of work on posthumanism in last decade that has moved the discourse of posthumanism and animals and beyond animal activism. The discussion has become more scholarly, and more interesting in terms of human-animal relationships,” Grant explains.

Theorists are now considering the way that laborers are treated and how race is stratified in regards to the animal-human divide, Grant adds.

The study of gender, too, is factoring into current examinations of human exceptionalism. One example Grant points out is that slurs against women are animal-based and suggest that women are animalistic and thus subhuman.

The contributing authors’ respective chapters diligently seek to interrogate and destabilize these biases.

Jungkunz adds that more broadly, many marginalized groups suffer because of the widespread notion of exceptionalism.

“Marginalized groups will be compared to animals, thereby attempting to define such groups as somehow subhuman, or inferior,” Jungkunz explains. “The animal/human binary has been devastating for animals, as well as many people who have been unjustly defined by dominant forces. It needs challenging.”

Goals for the Book

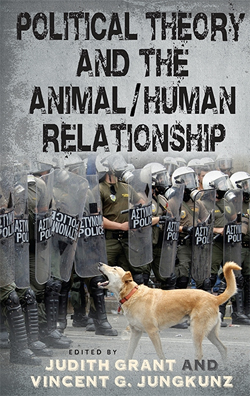

One of the goals for the volume, Grant and Jungkunz note, is to consider the space in which animal subjectivity intersects with human subjectivity. Grant points out the significance of the volume’s cover photo, which depicts a dog who was frequently spotted at riots in Greece.

The dog, surrounded by police officers clad in riot gear, was “always on side of protestors,” Grant explains.

The dog, surrounded by police officers clad in riot gear, was “always on side of protestors,” Grant explains.

“He was a stray and became the unofficial mascot of the protests,” Grant remarks. “The photo evokes an animal coming up against ‘the Man,’ coming up against human authority. One of the issues we’re interested in is the way that the treatment of immigrant laborers is mirrored in the treatment of animals.”

One of the target audiences for the book is, of course, academic critical theorists, especially those who specialize in political theory.

More broadly, though, Grant and Jungkunz hope the book speaks to “anyone who studies social political theory or is interested in posthumanist questions,” Grant explains.

‘Take Animal Subjectivity and Agency Seriously’

The book does not intend to provide a prescriptive list of recommendations or possible courses of action, the editors note. Rather, “It is perhaps to plead to take animal subjectivity and agency seriously in political discussions. Animals do have an interest in political outcomes. They are not just passive objects to be acted upon,” Grant explains.

Jungkunz adds that the book does the important work of showing the devastating consequences of ignoring animals’ voices and needs.

“The animal/human binary […] has justified so many ‘regimes of truth’—narratives, discourses, institutions, people who have created many exclusions using this structure, exclusions that have led to various violences against those deemed animalistic, or subhuman, as well as against the very environment that gives us life,” he remarks.

The volume also takes into consideration questions and definitions of personhood which, Grant notes, must be determined through enlightened discussion about the status of animals and their stake in the political issues of the day.

Political Theory and the Animal/Human Relationship is currently available in hardcover and paperback via the SUNY Press website and as a Kindle book via Amazon.

Comments