The 2017 Spring Literary Festival welcomes author Colm Tóibín for a lecture on Wednesday, April 5, at 7:30 p.m., in Walter Hall Rotunda, and for a reading on Friday, April 7, at 8:30 p.m., in Baker Theatre.

By Justin Mundhenk

Graduate student pursuing a Ph.D. in Creative Writing: Fiction

Writers get written into corners by genre, style, and subject matter, and sometimes by the stereotypes long associated with artists in general. Perhaps one label all writers would gladly wear is that of a worker. It certainly isn’t the sexiest or most provocative. It won’t grab headlines in the Twitter Age. It does, however, show dedication to the thing we treasure most—the written word. Colm Tóibín is a worker, plain and simple. He is a writer at work.

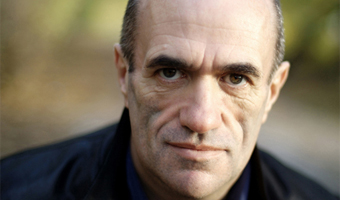

Colm Tóibín

This becomes obvious with a simple glance at his output so far: eight novels, two story collections, essay collections, plays, and a memoir. The work has made Tóibín a New York Times bestselling author. He won the 2004 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for his novel, The Master. He has been shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize three times, and his novel, Brooklyn—recipient of the Costa Novel Award—was adapted to film and released to acclaim in 2015. And like many writers at work, Tóibín seems to be circling the same set of ideas in various forms over time. His work often focuses on death, sexuality, family, and a persistent longing to find one’s self comfortably at home, wherever that might be. His newest novel, due out next month, is House of Names, a recasting of the Clytemnestra story, and it continues along those lines in a provocative way.

In a 2016 interview for the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, Tóibín described the writing process as something akin to music. The writer seeks out a rhythm or melody, and once that’s established, all that’s needed is “slow, careful work.” He adds that “Every sentence creates both a solution and a problem for the next sentence. It can’t be exactly the same.” Reading Tóibín, one can’t help but notice the rhythmic nature of his prose, as if he has his ear close to the page when he writes. Each sentence calls to the one that follows and responds to its precedent, plunging us further into the world of the story and a character’s complexity. The language is unadorned yet rich in its simplicity. Consider this passage from his most recent novel, Nora Webster:

She drove to Cush in the old A40 one Saturday that October, leaving the boys playing with friends and telling no one where she was going. Her aim in those months, autumn leading to winter, was to manage for the boys’ sake and maybe her own sake too to hold back tears. Her crying as though for no reason frightened the boys and disturbed them as they gradually became used to their father not being there. She realized now that they had come to behave as if everything was normal, as if nothing were really missing. They had learned to disguise how they felt. She, in turn, had learned to recognize danger signs, thoughts that would lead to other thoughts. She measured her success with the boys by how much she could control her feelings.

Nora Webster is also a perfect example of Tóibín’s patience as a writer. He wrote the first chapter in 2000, and finished the book in September of 2013. In an interview with The Guardian, he revealed that, between beginning and completion, he managed to write two other novels, two story collections, and a play. These other works, however, were always “circling the story that was Nora Webster’s, working out ways of writing about family and loss and trauma.” For Tóibín, the work never seems to be done; instead, it’s only a matter of time until he complements the old familiar melody with another set of lovely harmonies.

In her review of Nora Webster for The New York Times, Jennifer Egan addressed the novel’s steady, deliberate unfolding: “The absence of melodrama brings these discoveries into relief, and the sense of life flowing around them, by turns meandering and rushing, gives the illusion that Tóibín’s carefully engineered novel is unfolding with the same erratic rhythms as actual life.” This is what happens when a writer allows a story to grow on its own accord and find its own shape. The story takes on qualities of liveliness as Tóibín steadily examines and seems to immerse himself in one woman’s grief in a small town in Ireland. Note, too, Egan’s subtle contrast between “illusion” and “carefully engineered,” as that is often the standard of good fiction: a story that feels unencumbered by the artist’s hand. In Tóibín’s work, we’re allowed to settle into a world that is familiar and realized. It becomes our world, our life, our story, but that verisimilitude can only be achieved with acute attention to detail and emotion.

Tóibín’s writing always explores the push and pull of loss. Death pushes us forward into a future unknown, a future that, in the midst of grief, we can even welcome. The novel begins shortly after the death of Nora Webster’s husband and her children’s father, Maurice. Her home, her children, and the small town they live in are all reminders of her grief, and she becomes acutely aware of her loss when friends and family visit to offer condolences and support. During one such visit from her aunt, Nora Webster loses track of their conversation to wonder “if there was somewhere she could go, if there was a town, or a part of Dublin with a house like this one, a modest semi-detached house on a road lined with trees, where no one could visit them and they could be alone there, all three of them.” If such a home could be found, it “would include the idea that what had happened could be erased, that the burden that was on her now could be lifted, that the past could be restored and could make its way effortlessly into a painless present.” The unknown, Nora Webster seems to think, allows us to contemplate a new life unburdened by memory and the ghosts that haunt us.

But death is also constantly pulling us back into the past. We must return to the memories that sustain a life even after it’s gone. Watching films with her two sons conjures up new meanings and harsh reminders for Nora, and after viewing Gaslight, the boys in bed, Nora realizes that “[e]very room, every sound, every piece of space, was filled not only with what had been lost, but with the years themselves, and the days.” We can often go through our day without examining the history inflecting our daily lives, but grief has a way of imprinting itself on every object. Home is where we live, but it is also a reminder of the homes we have lost.

In “One Minus One,” a story originally published by The New Yorker, and subsequently found in The Empty Family, we see Tóibín once again investigating the impact of death and notions of home. The story, in which the narrator recounts his return to Ireland in his mother’s final days, takes place six years after the mother’s death.

takes place six years after the death of the narrator’s mother, and in it he recounts his return to Ireland in his mother’s final days. We learn that the narrator’s relationship with his family is strained, and that “going home . . . would not be simple, that some of our loves and attachments are elemental and beyond our choosing, and for that very reason they come spiced with pain and regret and need and hollowness and a feeling so close to anger as I will ever be able to manage.” Regret lies at the heart of this particular story. It is a regret born of distance and separation, brought on by the hard fact of death. The story ends with the narrator recalling his return to New York after his mother’s burial. Six years removed, the narrator comes as close to epiphany as he can get: “I saw that it was too late now, too late for everything. I would not be given a second chance. In the hours when I woke, I have to tell you that this struck me almost with relief.”

For Tóibín, death is often a narrative starting point for introspection, and it carries along with it guilt and regret and a seemingly strong dose of helplessness. But there is some hope too. Nora Webster finds her voice, singing again for the first time in years. Eventually she must face her husband’s ghost, but in doing so, she’s able to move on and shape a new home for her family. Perhaps that’s what Tóibín’s really studying: the ways in which we must confront our ghosts. Such confrontation won’t necessarily bring redemption or relief, but it will allow for a new understanding of ourselves. One can only hope, expect even, that Tóibín will continue this exploration in the only way he knows how, with generous listening, his considerable artistry, and dogged persistence.

Comments