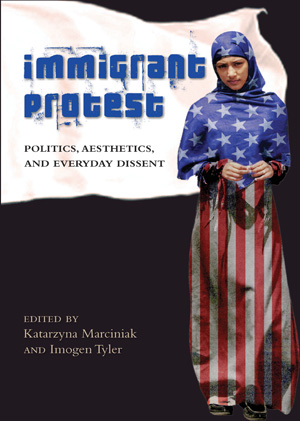

Dr. Katarzyna Marciniak’s new book “Immigrant Protest: Politics, Aesthetics, and Everyday Dissent” explores how political activism, art, and popular culture challenge the discrimination and injustice faced by “illegal” and displaced peoples.

The Ohio University Women’s Center hosts an International Women’s Coffee Hour and Book Party featuring Marciniak on Wednesday, Nov. 19, from 4 to 6 p.m. in the Women’s Center in Baker Center 430.

The Ohio University Women’s Center hosts an International Women’s Coffee Hour and Book Party featuring Marciniak on Wednesday, Nov. 19, from 4 to 6 p.m. in the Women’s Center in Baker Center 430.

The last decade has witnessed a global explosion of immigrant protests, political mobilizations by irregular migrants and pro-migrant activists. This volume, co-edited by Marciniak and Imogen Tyler, considers the implications of these struggles for critical understandings of citizenship and borders. Scholars, visual and performance artists, and activists explore the ways in which political activism, art, and popular culture can work to challenge the multiple forms of discrimination and injustice faced by “illegal” and displaced peoples. They focus on a wide range of topics, including desire and neo-colonial violence in film, visibility and representation, pedagogical function of protest, and the role of the arts and artists in the explosion of political protests that challenge the precarious nature of migrant life in the Global North. They also examine shifting practices of boundary making and boundary taking, changing meanings and lived experiences of citizenship, arguing for a noborder politics enacted through a “noborder scholarship.”

Marciniak, Professor of Transnational Studies in the English Department at Ohio University, has previously authored Alienhood: Citizenship, Exile, and the Logic of Difference and Transnational Feminism in Film and Media.

Invisibility and Blindness

Marciniak and Tyler introduce their book with the graphic symbolism of invisibility and blindness as portrayed in filmmaker Robert Rodriguez’ 2010 action film Machete. “The motif of a jabbed eye, a blinded eye, underlines the ocular discomfort that characterizes the narrative as the film plays with the idea that eye jabbing enacts both immigrant and anti‑immigrant rage.”

“While Machete is a fictional film about migrant revenge, it foregrounds the existing conditions of hostility, suspicion, and violence faced by many irregular migrants in the United States,” they write. They also cite economic inequalities around the world—and increasing securitization of borders—that have led to migrant protests in response to “the deteriorating conditions for refugees, asylum seekers, economic and other unwanted and irregular migrants” in France, Latin America, Italy, Greece, Spain and more.

In their introduction they quote Ruben Andersson: “To capture the paradoxes of today’s migrations, which seem to pound against the walls of our reality, we might similarly need to break through the conventions that have defined so much research, activism, art and journalism concerned with migration.”

“He argues that it is necessary to focus on ‘the energy, creativity and determination of migrants themselves’ as well as to engage in what he terms ‘stylistic and methodological promiscuity’ in order to break through the limits of disciplinary research. Andersson’s point about ‘stylistic and methodological promiscuity’ most compellingly describes the spirit of our book. The energy of the collection is driven precisely by immigrant voices that actively resist mainstream representations of immigrants as bodies without emotional complexities, too often boxed into binaries such as ‘passive’ or ‘criminal.’ The (chapter) authors go beyond eschewing such superficialities and instead mock them, from artistic play with the veil to ironic representations of migrant labor, to outrageous performances of ‘good citizen”’ and ‘bad migrant.’ From the outset, our intention has been to create a project that, like Rodriguez’s Machete, is an unapologetic fusion of styles that provoke with the breadth of disciplinary employment and depart from ways of creating knowledges that too often rely on one theoretical paradigm, discipline, or region. Through its form and content, the book argues for a noborder politics which has to be enacted through a noborder scholarship.”

Noborder Scholarship

“Noborder scholarship must push through the limits of disciplinary boundaries, must honor intellectual messiness, demand agility, fluidity, situationality; it must create new conceptual bridges,” Marciniak and Tyler write.

“The building of such new bridges is always about methodological innovations and thus about methodological pleasures and risks. And noborder scholarship must embrace those risks. Bridges demand that we resist the temptation to think of knowledge in territorial ways. The productive risks associated with such methodological ‘promiscuity’ entail dislodging the fields of study from their accepted boundaries and from the defenses of those boundaries.”

In their afterward, Marciniak and Tyler conclude, “One of the major themes of this book has been in/visibility and, in particular, the centrality of representations and perceptual frames in creating value and prescribing differential values to human lives….

“The intensification of the migrant protests documented in this book form one tiny part of a growing number of uprisings, movements, and moments by disenfranchised people and their allies against neoliberal social and economic policies around the world. Immigrant Protest has sought to map the diversity and vitality of migrant protests against border and citizenship regimes in a range of places, mediums, and contexts. We have highlighted some of the extraordinary and creative means through which migrants, citizens, artists, activists, and scholars engage in acts of resistance in a range of exceptional and everyday contexts. The recording and restaging of migrant protests in books such as this is a critical part of ‘No One Is Illegal’ movement—a movement that urgently requires the invention of ‘new idioms of the political, and of belonging itself’ (Berlant 2011, 262).

“As art activist Irina Contreras notes in a beautiful essay about her work titled ‘Cycles of Invisible Resistance’: ‘There are ways in which the rigor of research and storytelling reclaims something. This work cannot fix everything, but it feels like part of a process, a step towards healing’ (Contreras 2012, 329). We know that equality and justice require transformations in the relations ‘between words and things, between words and the visible’ and a reorganization of ‘the sensory configuration of what is given to us and how we can make sense of it’ (Rancière 2008, 174). Documenting resistance and protest involves the creation of new aesthetics of migration, which, in turn, can be used to question the inclusive/exclusive logic of citizenship and the language and economics of illegality.”

Comments