As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) prepares to announce its Fifth Assessment Report from Working Group I on Friday, Sept. 27, in Stockholm, researchers continue to test hypotheses that help shape the climate change picture.

Dr. Sarah Davis, Assistant Professor in the Voinovich School of Leadership and Public Affairs and Research Assistant Professor in Environmental and Plant Biology, talked with a colloquium audience Sept. 20 about using experimentation to develop models for how much carbon farmland and forests absorb from the atmosphere.

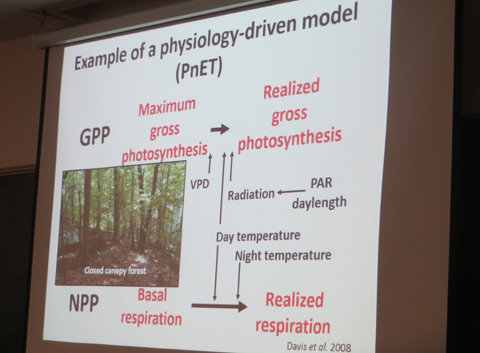

Plants act as carbon sinks through photosynthesis, a process that is important for understanding both how the ecosystems are reacting to the increased carbon in the atmosphere and how management of those ecosystems affects carbon storage.

The new IPCC will revisit terrestrial carbon dynamics and feedbacks between the atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions and ecosystems.

“The long-term response of forests to climate change is not well understood,” Davis said, “and the effects of land use change are uncertain.”

Davis is looking at both the below-ground carbon stocks in agro-ecosystems (agriculture) and above-ground carbon stocks in forested ecosystems.

Agriculture: Strategies for Increasing Carbon Sinking

In the below-ground model, Davis notes that the part of the ecosystem that stays year after year is the soil, so she is looking at alternative bioenergy cropping systems that might increase soil organic carbon with “judicious management.”

Davis cites Brazilian sugarcane farms, where the land management has changed as a result of eliminating the practice of burning cane before harvest, as an example of “a single land management decision that completely reverses carbon fluxes of the landscape and results in a net carbon sink.”

She studied miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus), a perennial grass that can be used for biofuel production, comparing it with corn and switch grass, also biofuels, to determine the net carbon sink involved in the agricultural production. Miscanthus stores more carbon underground than the other biofuels, and thus has a greater net carbon sink.

How Do Forests Respond to Climate Change Over Time?

Davis’ current work in forest ecosystems focuses on the question: “How do forests respond to climate change over time?”

In the forest, carbon is stored above ground in the biomass of the trees, and changes occur slowly. Davis is using a chronosequence study to look at what happens to carbon during forest succession.

With low-intensity harvesting and management in mixed hardwood forests, she found in a 2009 study, carbon sequestration is similar to un-harvested forests. In plantation systems, however, such as those usually planted with pine, repeated harvests result in a net flux of carbon to the atmosphere.

Forests: The ‘Missing Carbon Sink’

Over the past decade, researchers were looking for “the missing carbon sink” after calculations showed that about half of the 9 billion tons of carbon produced each year was unaccounted for, but some of what used to be termed missing carbon “we now know is in the forests of the eastern U.S., with a large portion also in the ocean,” Davis explained.

According to a National Geographic article: “Each year humanity dumps roughly 8.8 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, 6.5 billion tons from fossil fuels and 1.5 billion from deforestation. But less than half that total, 3.2 billion tons, remains in the atmosphere to warm the planet. Where is the missing carbon?”

Davis notes that much of the Eastern U.S. forest has regenerated since the 1900s, (See story on Dr. James Dyer’s work on: Eastern Forests Are on the Move—Here Come the Maples.) and as result has been an important carbon sink.

Davis is testing the hypothesis that aging forests might be responding more aggressively to the new carbon-rich atmosphere compared with the younger forests that have grown up with more atmospheric CO2.

One big unknown, Davis says, is that “today a young forest has never experienced the lower concentration of CO2 that the old forest experienced.” Tree photosynthesis declines with age, she notes, but her current study of pine trees in North Carolina involves recent forest succession in the carbon-rich environment. “But if we look back in time” to look at the characteristics of old forests when they were young, “the only information we have is in the woody annual increment cores of the trees, which provide a signature of the physiological activity.”

“The question I have is: Do young and old forests respond similarly to climate change?”

“We only have data about physiological responses of young forests to elevated CO2. We don’t know the response for old forests,” she said. “The response of older forests to elevated CO2 might actually be greater compared to what we’re seeing with younger forests. Older forests might be getting greater returns.”

Further studies are needed, she says, to look at whether these trends will continue in the aging hardwood forests—and to determine the ability of the Eastern U.S. forests to respond to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Davis is a new faculty member at Ohio University, with her primary appointment in the Environmental Studies Program of the Voinovich School for Leadership and Public Affairs. She is an ecosystem ecologist with expertise in energy bioscience, biogeochemistry and eco-physiology.

One Comment